Patients who choose robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy (RARP) believe it’s the best way to eradicate prostate cancer (PCa). In their mind, this equates to a cure. In fact, PCa can recur (come back) as long as 15 or more years after any whole-gland treatment. Increasingly, no one talks about “cure” anymore. Instead, “success” is defined as biochemical control, meaning all follow-up PSA results are less than or equal to 0.2 ng/mL. But, if PSA rises above 0.2 ng/mL, it’s biochemical recurrence (BCR) because PSA is a biomarker indicating PCa growing somewhere in the body after whole gland curative intent treatment. On the other hand, if PSA holds steady at ? 0.2 ng/ML, it’s called a biochemical recurrence-free (BCRF) outcome. Therefore, published clinical studies now generally report outcomes so in terms of BF or BCRF. Thus,

- High BCR statistics = high failure rates

- High BCRF statistics = high success rates

Two clinical predictors of BCR are higher Gleason scores or more extensive tumor stage. Post-treatment outcome success data falls as time goes by, likely due to the diagnostic inaccuracy of conventional TRUS biopsy, which misses or under-detects the most aggressive PCa and the exact extent of the tumor. Thus, patients who were originally diagnosed as Gleason 3+3 or stage T2b before RARP may be found with more aggressive or extensive PCa at the time of surgery, when the actual prostate specimen is removed and analyzed. This increased failure rate occurs more often than patients know.

A 2013 study by Kim et al. reports 5-year oncologic control from a study of 175 patients who all had RARP and no other therapy (hormones or radiation) during the study period.[i] This study is a good example of upstaging, and other studies confirm their data. Enrolled patients all had a TRUS biopsy. Based on biopsy pathology (tissue analysis), the 175 patients made up the cohort as follows:

- 110 patients (62.5%) with Gleason ≤6

- 42 patients (24.4%) with Gleason 7

- 23 patients (13.1%) with Gleason > 8

After RARP, when the whole prostate specimens were examined, based on final pathology, 25 of the Gleason 6 patients were upgraded to Gleason 7, and 4 were even upgraded to Gleason 8-10. In short, 28.1% of patients were upgraded to more aggressive disease than what they were diagnosed with!

One other factor that puts a prostatectomy patient at increased risk for BCR is the location of the tumor at the time of RARP. Either capsular penetration (tumor cells at the outer margin of the gland, also called positive surgical margins or extracapsular extension (ECE or tumor found growing in the tissue beyond the prostate capsule) raises BCR risk. Worse still, if both are present the risk for BCR is much higher. In the Kim study, positive surgical margins were found in 59 patients (33.5%), or one-third of the study population.

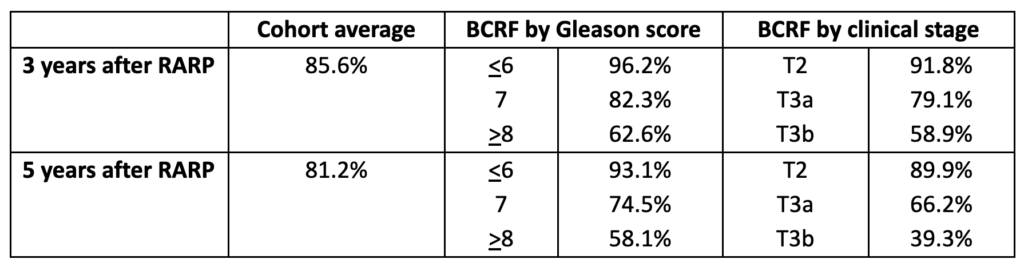

The authors report their 3-year and 5-year results according to both Gleason score and clinical stage. Note that failure rates between 3 years follow-up to 5 years. The sad part is, once BCR becomes evident after surgery, the number of “salvage” options with good long-term success is very limited, so the potential for “cure” evaporates. The challenge becomes finding where the PCa is, and hoping that if it is still in the prostate bed, a course of radiation will destroy the remaining cancer. It can be devastating for patients who went through robotic prostatectomy, and whatever side effects they endured during recovery, to have their annual PSA test in the fourth or seventh or eleventh year after surgery reveal PSA > 0.2 ng/mL, just when they thought they were “cured”.

Here is a summary of their oncologic control rates, expressed as BCR-free (BCRF):

The 74.5% BCRF rate for the Gleason 7 patients at 5 years means that 25.5%, or fully a quarter of the intermediate risk patients, had biochemical recurrence as soon as five years after surgery. For comparison, here are group averages (across low, medium and high-risk disease) from 3 other studies:

- Sooriakumaran et al. (2012) – 944 patients with an average 84.8% BCRF at 5 years[ii]

- Suardi et al. (2012) – 184 patients with a group average of 86% BCRF at 5 years[iii]

- Menon et al. (2010) – 1384 patients with a group average of 86.6% BCRF at 5 years[iv]

Today’s advances may eliminate surgery disappointments

There is no one-size-fits-all PCa treatment. Best treatment outcomes happen when the treatment is matched to the disease – which means the diagnosis must be as accurate as possible. Think of the patients in the Kim study: 29 were upgraded, and 59 had positive surgical margins at the time of surgery. If this had been known in advance, treatment strategy could have been changed.

Today, three advances assure a much more specific and accurate diagnosis than TRUS biopsy:

- 3T multiparametric MRI (3T mpMRI) reveals information that is essential before a biopsy. This type of imaging not only shows the gland anatomy and any suspected PCa lesion, but it also offers important tissue characterizations in terms of how aggressive the lesion may be. On the other hand, if no suspected lesion is revealed, there is no need at that time for a biopsy; monitoring by PSA and mpMRI can continue.

- In-bore MRI-guided targeted biopsy done in real time inside the tunnel of the magnet is far superior to TRUS biopsy. The MRI guided biopsy uses minimal needles directed precisely into areas of the lesion most likely to harbor aggressive cells. This reduces both the risk of infection and the risk of missing (under-detecting) aggressive disease.

- Genomic analysis can identify molecular factors that point to potentially lethal disease, especially given both the image-based information from mpMRI, and a pathology report that signals the need for further analysis.

A fourth advance, Focal Laser Ablation (FLA) is a precise, minimally invasive MRI-guided treatment that destroys the PCa with minimum to no side effects. No general anesthesia is needed. In addition to being an outpatient procedure with a very rapid recovery time, it also has the advantage of keeping all future treatment options open – including RARP.

There are two key takeaway messages:

- Radical prostatectomy, including robotic-assisted radical prostatectomy, can never guarantee “cure” but patients must be monitored for biochemical recurrence, even late-onset BCR.

- mpMRI before prostatectomy can identify tumor that is at the gland margin, has penetrated it, or has begun to extend beyond the capsule and is growing in the prostate bed. When the imaging is done on a powerful, state-of-the-art magnet and interpreted by an expert reader, it is possible to know before RALP what could not have been revealed by TRUS biopsy. It seems inexcusable to send any PCa patient for surgery without first obtaining this information.

The Kim study is a cautionary tale. I hope this explanation helps in understanding what it’s all about.

NOTE: This content is solely for purposes of information and does not substitute for diagnostic or medical advice. Talk to your doctor if you are experiencing pelvic pain, or have any other health concerns or questions of a personal medical nature.

References

[i] Kim KH, Lim SK, Shin TY, Chung BH et al. Biochemical outcomes after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy in patients with follow-up more than 5-years. Asian J Androl. 2013 May;15(3):404-8.

[ii] Sooriakumaran P, Haendler L, Nybert T, Bronberg H et al. Biochemical recurrence after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy in a European single-centre cohort with a minimum follow-up time of 5 years. Eur Urol. 2012 Nov;62(5):768-74.

[iii] Suardi N, Ficarra V, Willemsen P, De Wil P et al. Long-term biochemical recurrence rates after robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: analysis of a single-center series of patients with a minimum follow-up of 5 years. Urology. 2012 Jan;79(1):133-8.

[iv] Menon M, Bhandari M, Gupta N, Lane Z et al. Biochemical recurrence following robot-assisted radical prostatectomy: analysis of 1384 patients with a median 5-year follow-up. Eur Urol. 2010 Dec;58(6):838-46.